Impending crisis of aging doctors treating aging patients

How IT can help aging health care workers

Japan's long-aging society continues to move into uncharted territory. The public and private sectors aim to create a vibrant and long-lived society, but there are many obstacles and one of them is medical care. The risk of losing access to adequate medical care is growing, and not just because of the possibility of a financial crisis.

Along with the rest of society, Japan's doctors are getting older, and their decreasing physical capacity is reducing the amount of medical care they can provide. Ro-ro-kaigo, or old-to-old nursing, is a recently popularized term that refers to seniors taking care of other elders. A similar trend is emerging in healthcare. Elderly doctors treating elderly patients, Ro-ro-iryo, is set to become a major issue in large cities.

In 2026, the amount of medical treatment per person aged 75 or older living in a large city is expected to decrease by 20% from what was given in 2016, in terms of time, according to a Nikkei analysis. Japan needs to find treatments for these issues through deregulation, increasing the number of nurses assisting doctors and more widespread use of online medical care.

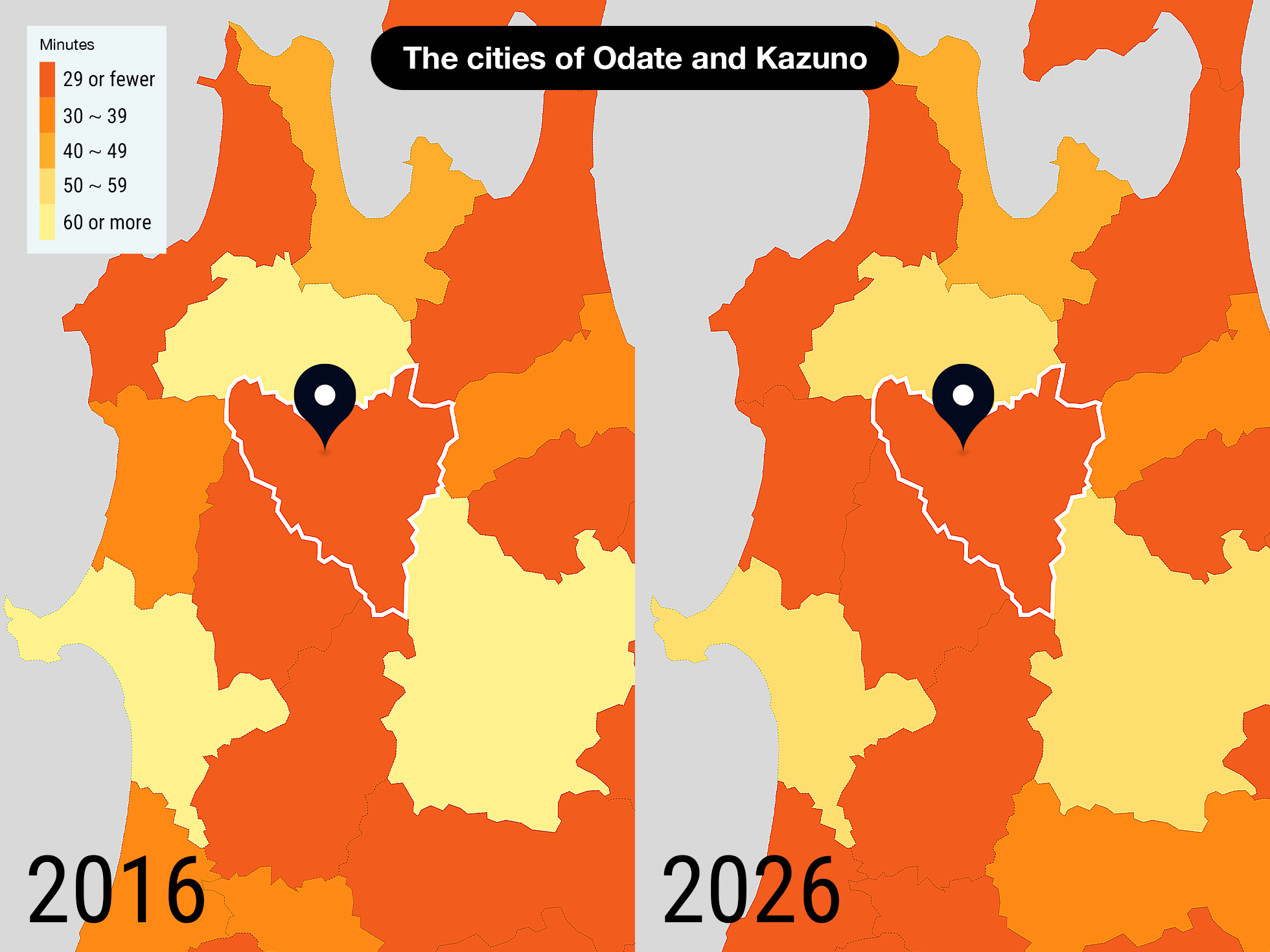

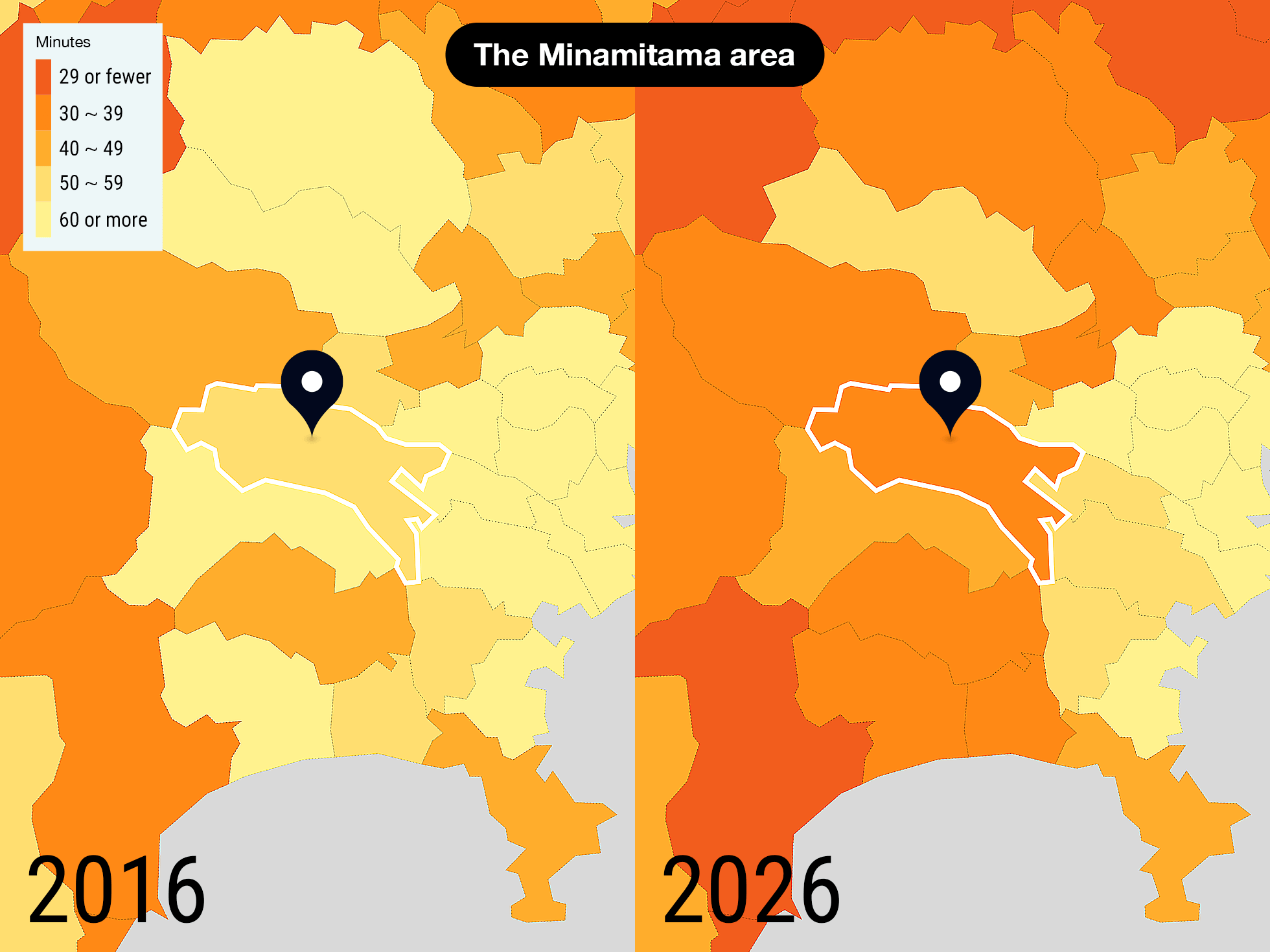

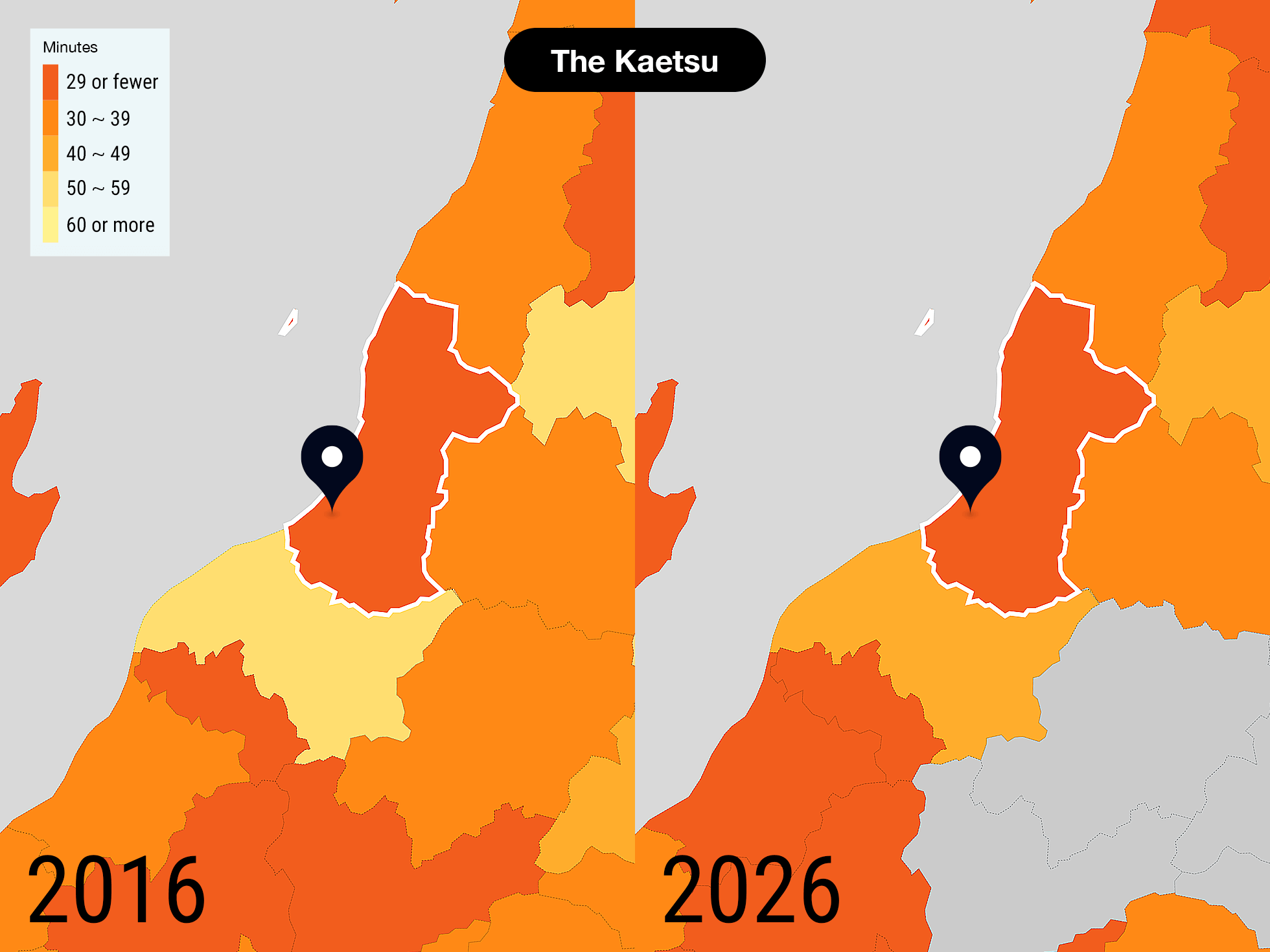

Amount of time physicians can spend on each resident aged 75 or older (per week)

- No Data

- 60 or more(large city level)

- 50-59(rural city level)

- 40-49(extremely rural city level)

- 30-39(in underpopulated areas)

- 29 or fewer(in extremely underpopulated areas)

2026

Treatment time drops by 20%

Treatment time drops by 20%

'underpopulated areas' expand

Rather than simply looking at the numbers of doctors and residents, Nikkei attempted to capture changes in the supply of and demand for healthcare by looking at doctors' total working hours and the elderly population in the later stages of life. Considering the age of physicians, the total amount of time spent providing medical care does not increase as much as the growth in the number of doctors. But the elderly are more likely to become ill, and the number of patients can quickly increase. Sparsely populated areas are known to have severe doctor shortages, while big cities are thought to be in a better position. In the future, however, even major cities will experience rapidly aging populations. This leads to the assumption that the amount of time doctors will be able to devote to providing medical care will decrease.

With the help of Tai Takahashi, a professor at International University of Health and Welfare and a specialist in regional healthcare, Nikkei analyzed the working hours and population distribution of physicians in Japan's 344 "secondary medical areas." These are prefecturally designated administrative districts made up of neighboring municipalities. Using this analysis, Nikkei estimated the amount of time per week that doctors will be able to spend treating elderly patients in 2026.

In large cities, much like in rural regions, doctors in many areas are expected to have less time to devote to medical care.

Let us first look at 2016. The average consultation time in Japan's 52 metropolitan medical areas, those with 1 million or more residents, was 78.1 minutes. In the country's 166 medical areas in rural cities and 126 areas in underpopulated areas, the averages were 57.2 and 31.7 minutes, respectively. Using this as a benchmark, areas where the average is less than 30 minutes were classified as "level of extremely underpopulated areas." Using 10-minute increments, areas were grouped into this and five other levels: underpopulated areas, extremely rural cities, rural cities and large cities. The "large city level" average is 60 minutes or more.

Of the 52 metropolitan areas, at this point 32 were at the "large city level" in terms of medical care time per senior citizen. Nine were already at the "rural city level," 10 were at the "extremely rural city level" and one was at the "extremely underpopulated area level."

Dramatic changes are in store by 2026. The average consultation time in metropolitan medical areas falls to 63.4 minutes, a 19% drop. This is a greater decline than the average in areas in rural cities, which falls 14%, and in underpopulated areas, where it decreases by 12%. The number of medical areas in the "extremely rural city level" increases to 12 from 10, and the number in the "underpopulated areas level" rises to ten from zero.

"In 2026, the last of Japan's baby boomers will turn 75. Conditions will become more difficult in the bed towns around large cities, where many from that generation live," Takahashi predicts.

The shortage of doctors is growing faster in major urban areas relative to other areas.

Average medical care time per resident aged 75 or older by medical area type

In Shonan seibu, which includes the cities of Hiratsuka and Hadano in Kanagawa Prefecture, next to Tokyo, the average will drop to 39.3 minutes from 61.6 minutes in 2016, a sharp decline that will land the area in the "underpopulated area level." Tokyo's Minamitama area, which includes the cities of Hachioji and Machida, and Saitama Prefecture's Nanseibu area, which covers the cities of Wako and Asaka, and Tobu area, which includes Koshigaya and Misato, are also expected to fall to this level.

What kind of issues are appearing as doctors age and have to care for elderly patients? To check on this, let us look at the Tohoku region in northeastern Japan.

A glimpse of the future in Akita

A glimpse of the future in Akita

A 78-year-old surgeon at the operating table

In northern Akita Prefecture, there is a secondary medical area made up of the cities of Odate and Kazuno. 36% of the residents are 65 or older. With one in three physicians 60 or older, it is the model medical area in which older doctors care for older patients. The treatment time per person 75 or older was an extremely short 23.5 minutes in 2016.

Shuichi Yoshihara, the 64-year-old director of the Odate City General Hospital, betrayed a hint of fatigue when he spoke. "The number of general practitioners in the area has dropped by two-thirds compared to 10 years ago, and the average age is now 70," he said. "People who can't get seen at local clinics come here, and it's always crowded." Some doctors are unable to work because of health issues related to the excessive workload, and the hospital makes up for them by rehiring older doctors. Until 2019, a 78-year-old doctor was still using a surgeon's scalpel.

Then the new coronavirus hit the already struggling workforce. The hospital is designated to handle patients with infectious diseases, so doctors had to be available to work until late into the night. Some surgeries had to be postponed.

As residents age, the number of patients with complications rises. "Some patients need to get diagnoses from multiple departments," Yoshihara said. "The burden on doctors is really increasing."

At Akita Rosai Hospital 10 km to the southeast, the situation is the same. 62-year-old Koichiro Okuyama, an orthopedic surgeon and director of the hospital, still goes into surgery two days a week. There is no full-time doctor of internal medicine, so Okuyama often sees dialysis patients who must frequently visit the hospital. "I'll be an internal doctor, along with a psychiatrist," he said. "I have to use all of the skills I learned during my residency."

"I can do my job because I love it," he said with a laugh, but as he grows older, it will become more difficult to make up for the shortage of doctors with his enthusiasm alone.

These strained conditions are the future of healthcare in rural cities and urban areas.

Moreover, the rate at which people 75 or older receive medical treatment is three to six times higher than that of 10- to 39-year-olds (per 100,000 patients), according to the health ministry. The time required to perform their treatments increases by that amount. There is a growing concern that the labor shortage already affecting underpopulated areas will spread nationwide.

The number of doctors will increase,

with the share of 60+ age group up

- Actual measurement

- Forecast

However, failing to account for the factor of age and track changes will lead to an erroneous assessment of the actual conditions.

Let us take a closer look. In the decade leading up to 2018, the overall number of physicians increased by 14%, but the number of physicians 59 or younger grew only 5%. Older doctors cannot work long hours. Including being on call, male doctors in their 40s work more than 70 hours per week, but that drops to between 50 and 60 hours when they reach their 60s.

Moreover, the rate at which people 75 or older receive medical treatment is three to six times higher than that of 10- to 39-year-olds (per 100,000 patients). The time required to perform their treatments increases by that amount. There is a growing concern that the labor shortage already affecting underpopulated areas will spread nationwide.

Doctors' average working hours get shorter as they get older

Source: Survey of doctors' working conditions and ideas on workstyle

The rate at which people 75 or older receive treatment is three to six times higher than for younger patients

per 100,000 people who receive treatment in one day

Hachioji

Hachioji

-- at-home medical care fails to draw young practitioners

The government is working to move medical care that can be done outside of hospitals to people's homes in an effort to check Japan's growing social welfare costs. As the field of home healthcare grows, so too does the scope of physicians' work. However, local infrastructure is still fragile.

The Minamitama secondary medical area, which includes the cities of Hachioji and Machida in Tokyo, is a metropolitan medical area. As of 2016, however, the time spent per person 75 or older was 51.4 minutes, which is in the "rural city level." In 2026, it is forecast to drop to 37.4 minutes, which will place it in the "underpopulated areas level."

"The number of patients who need home medical care is increasing, but there aren't enough general practitioners to support them," said Manabu Kazui, 63, who runs a clinic that provides home medical care. "There are also many hospitals that don't have anyone to take over the business."

There are about 20 doctors in the city who provide home medical care. More than half of them are in their 60s or older. Twelve general practitioners are on call 24 hours a day in case a home patient faces an emergency, but that system is hard on the older doctors. "Some of the doctors say, 'It'll cause a panic if I die,'" Kazui said.

There will be 245,000 people 75 or older in Hachioji in 2025, 1.5 times more than in 2015. While the number of doctors in their 60s and 70s will increase, the amount in their 30s and 40s is expected to drop.

The shock of workstyle reform hits Niigata

The shock of workstyle reform hits Niigata

In April 2019, laws covering workstyle reform went into effect. A regulation limiting overtime to an average of 80 hours per month will apply to doctors beginning in April 2024. Japanese physicians tend to work longer hours than their counterparts in other countries, with more than 40% of doctors who work at hospitals putting in more than 20 hours of overtime per week. Those long hours are an issue that needs to be addressed, but when that happens Japan's healthcare supply will drop.

"Nationwide, I don't think we'll be able to have the kind of work shifts we have now," said Yoshihisa Tsukada, director at Niigata Prefectural Shibata Hospital. He is growing increasingly concerned about the situation.

His hospital, which has 100 full-time doctors, also has an emergency room, which requires more working hours of the doctors. Seven doctors at the hospital exceeded the upper limit of their "Agreement on Overtime," and the hospital was told by the Labor Standards Inspection Office to correct the situation in December 2019. Hospital administrators reviewed the system of night and day shifts, got rid of 32-hour shifts and introduced a system of multiple attending physicians.

"When I was young, I was always learning, even if I was really pushing myself to the limit," Tsukada said. "Now I'm not sure I can keep up the quality of medical care."

Overtime tops 60 hours a week for some

Data on physicians' overtime per week

Japanese doctors tend to work longer hours than their U.S. counterparts

Data on physicians' working hours per week

Japan

U.S.

Online medical care is key

Online medical care is key

As both doctors and patients grow older, it seems Japan's physicians will be put into an ever-tighter bind. But there are solutions.

The first step is to increase the number of nurses assisting doctors. Since 2015, trained nurses have been able to perform insulin dosage adjustments, work that usually can only be performed by doctors. It's a system called "Specified Activities." It reduces physicians' workloads and also cuts down on the time nurses have to wait for instructions from doctors.

But as of the end of March 2019, only 1,700 nurses had received this training, far short of the government's goal of 100,000. In addition to a lack of understanding on the part of medical institutions, some have criticized the training as being too expensive. Additional support, such as subsidizing training costs or increasing the compensation of nurses who complete the training, is essential.

Nurses who have completed training in specified activities

Government Goal

100,000

Another promising option is online medical consultations, which were de facto permitted in 2015. They cut down on unnecessary hospital visits and make doctors more efficient.

"IT will be a great help in solving the shortage of physicians," said Daisuke Tanaka, an executive at Medley, a Tokyo-based company which develops online medical consultation systems. But among doctors there is significant resistance to online medicine, even after the ban on using it for initial examinations was temporarily lifted in response to the new coronavirus. Many believe that patients will flock to the most popular doctors, and the technology will create a gap between them and less IT-savvy physicians. To overcome the issue of aging doctors treating aging patients, it will be necessary to push ahead with deregulation. At the same time, doctors, the backbone of the medical system, must be ready to change with the times.