Japanese communities’ ability to look out for one another is disappearing

A rush to find more local welfare volunteers

Welfare volunteers in Japan are responsible for looking out for vulnerable people in local communities, such as seniors who live by themselves. In recent years, a growing number of municipalities have been unable to find enough volunteers. 54% of municipalities across Japan had vacant positions, according to a Nikkei investigation. If the number of vacancies continues to grow, there is a risk that community support will not be available for vulnerable populations during crises like the coronavirus pandemic or a natural disaster.

Welfare volunteers

Welfare volunteers

100 years of tradition

“Some volunteers cover thousands of households on their own,” said Hirofumi Ueno, a real estate agent who serves as the chair of the Welfare Commission in Toyosu, a popular residential area in Koto Ward on Tokyo Bay. He is heartbroken by the growing number of solitary deaths among the elderly in public housing. They sometimes go undetected for several days. He thinks that if someone spotted anything strange a bit sooner the deaths may have been prevented, but “we can’t cover the whole area very well.”

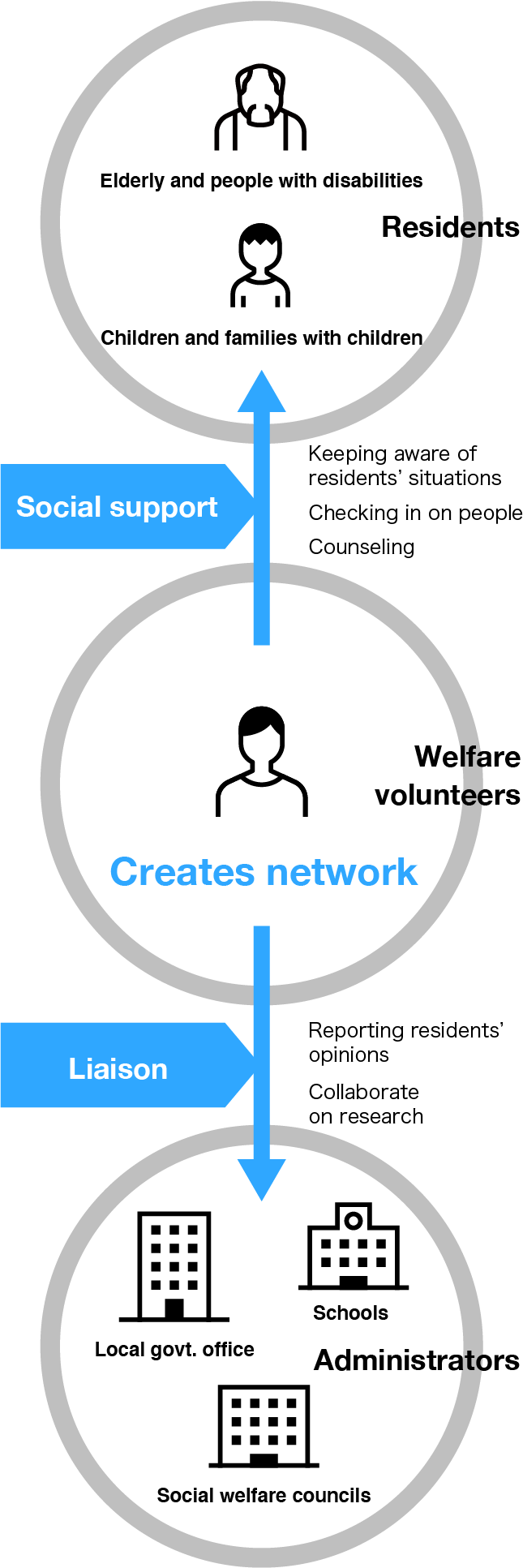

Welfare volunteers are part-time civil servants appointed by each municipality based on the recommendations of neighborhood associations and other organizations. They check in on senior citizens in the area and serve as a liaison with local welfare administrators. The details of the position are spelled out in the Commissioned Welfare Volunteers Law, and volunteers also double as “commissioned child welfare volunteers,” who deal with issues like child abuse. It is a traditional community monitoring system that has been in place for more than 100 years. They are officially civil servants, but they received no salary. Instead they are paid only enough to cover their expenses, such as transportation costs. Terms last for three years, and volunteers can be re-elected. The number of welfare volunteers for each area is set at the national level. There is one volunteer per 70 to 200 households in towns and villages, and one per 220 to 440 households in government-designated cities.

With the number of elderly living on by themselves is increasing, the government is promoting more home medical treatment and nursing care. The number of low-income, single-parent households is also increasing. Welfare volunteers, who go door-to-door and help people take advantage of welfare services, are more important than ever. However, their abilities are increasingly taxed. As of December 2019, there should have been about 218,000 volunteers, but only about 207,000 had been appointed. The national average vacancy rate, which had been about 1% until 2000, reached 4.9%.

Trends of welfare volunteer capacity and appointed volunteers

(Thousands of people)

Trend of welfare volunteer vacancy rate

(%)

Data through fiscal 2018 from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Report on Social Welfare Administration and Services,” data through the end of the fiscal year from Nikkei investigation

Vacant positions in

Vacant positions in

54% of municipalities

Some face shortfalls of 30%

At 23%, Okinawa had the highest vacancy rate among all prefectures. Some have suggested that is in part due to the delay in introducing the system to the prefecture while it was governed by the U.S. military, but the prefectural government says it has not been able to pinpoint a clear cause. Kanagawa Prefecture has the second highest vacancy rate at 8.6%, followed by Tokyo and Osaka, both major urban areas, at 8.5% and 7.4% respectively.

Nikkei also looked at municipalities for which there are no official statistics. When each prefecture was asked about vacant volunteer positions, 940 municipalities, or 54%, were reported to have open posts. 230 municipalities, or 13%, had not filled 10% or more of their positions. In some places the vacancy rate was more than 30%.

Breakdown of municipalities by vacancy rate

The situation is serious in urban areas. Among municipalities with 100,000 people or more, 48 have vacancy rates of 10% or more. That is 17% of such cities, higher than the national average. The highest vacancy rate was 33.8% in the city of Higashikurume in Tokyo Prefecture. That was followed by the city of Uruma in Okinawa at 30.7%, and Tama in Tokyo at 26%. Municipalities around Tokyo and in the Kansai area in western Japan feature prominently at the top of the list. Coastal areas in northern Japan that were hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami also have high vacancy rates.

Vacancies in municipalities by prefecture

- 30% or more

- 20% - less than 30%

- 10% - less than 20%

- Less than 10%

- No vacancies

Aging volunteers

Aging volunteers

Seniors keep working

Several factors affect the rising vacancy rates, especially those in urban areas.

Japan’s population has started dropping, but the number of households is still increasing. As a result, the number of volunteer positions, which is determined by the amount of households, is also growing.

But available workers are in short supply. “In the past, people who retired at the set age of 60 could take on these jobs,” said Akihiro Terada, an architect from Toshima Ward who serves as the chairman of the Tokyo Federation of Children’s Welfare Commissioners. “Now there are more people who keep working past 60, and it’s hard to find people to fill these positions.”

Local welfare volunteers by age

The percentage of welfare volunteers in their 70s was 20% in 2007, but it rose to 32% in 2016, according to a survey by the Tokyo-based National Federation of Children’s Welfare Commissioners. The share of volunteers in their 50s fell to less than half. Volunteers are in principle younger than the age of 75, and large numbers retire with each election every three years. Municipalities across the country are unable to replace them.

Large downtown apartments

Large downtown apartments

compounding the labor shortage

An influx of people into urban centers means downtown areas are filled with large housing developments. Koto Ward in Tokyo is a classic example. Koto has a vacancy rate of 18.2%, the highest among Tokyo’s 23 central wards. Each volunteer in the area covers an average of 1,060 households. Within the ward, the area of Toyosu has a remarkably high vacancy rate.

On reason for this is the rush of large apartment complexes being built there along Tokyo Bay, which are spring up alongside existing old public apartment complexes. According to the ward’s welfare department, many residents in large apartment complexes do not want to interact with their neighbors or join neighborhood associations. Officials added that aging among residents in public housing has also had a large impact on the situation.

Koto Ward’s local welfare volunteers by area

(%)

Many of Toyosu’s welfare volunteers are part of Japan’s baby boomer generation, and about half of them will reach the mandated retirement age at the end of the current three-year term. “We really need to find their replacements in a hurry,” said Ueno, the chair of the Welfare Commission in the area.

The situation is similar in Toshima Ward, which has the second highest vacancy rate among the 23 wards at 16.5%. “In addition to the large number of single elderly and foreign residents, the growing number of apartment buildings in the area of Ikebukuro has had an impact,” according to officials at the ward’s welfare and general affairs division.

Reducing burdens by

Reducing burdens by

rethinking operations

Moving online to draw more participation

“We need to change the thinking that being a welfare volunteer is for retirees,” said Kayoko Uenoya, emeritus professor at Doshisha University and a specialist in regional social welfare. Municipalities need to make it easier for people currently working to become volunteers by holding meetings and training in the evenings and on holidays. They should also consider reviewing the selection system, which relies on recommendations from neighborhood associations, and being more selective about volunteers’ duties to reduce their workload.

Efforts to address the shortage of volunteers are underway, starting with reducing the psychological burden of the position.

Shizuoka Prefecture introduced a cooperative system for welfare volunteers at the time of the 2019 election. Municipalities can appoint former volunteers and relatives of volunteers to help in activities like checking in on members of the community. There are now about 100 participating in the system. The system has spread to Hyogo Prefecture, the cities of Niigata and Chiba and elsewhere. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government is promoting a system in which volunteers in each area are divided into “groups,” and events are held within each group so new volunteers can consult with veteran members.

Some municipalities have started moving their operations online.

The city of Nonoichi is planning to lend tablet devices to all welfare volunteers by the end of the year. The goal is to make it easier for working people to participate in volunteer activities from their workplaces.

“In the past, many people felt guilty because they had to take time off from their regular jobs to join in the volunteer work,” said Nobuaki Higashi, chairman of the city’s Children’s Welfare Commission. The hope is that introducing tablets will help alleviate the shortage of volunteers. In the future, the city’s welfare volunteers want to move some of their other duties, such as looking after senior citizens, online too.

With the coronavirus pandemic and repeated natural disasters, local safety networks are becoming more important. The time has come for administrators and residents to think seriously about a new framework for welfare volunteers, who help keep communities bound tightly together.

Municipalities

(Darker color indicates higher vacancy rate)

Number of municipalities

(Example: Hokkaido)

Municipalities with vacancies

Total municipalities

61 / 179